The Center for Forensic Medicine at the Medical University of Vienna is the oldest forensic medicine institution in the world.

1044

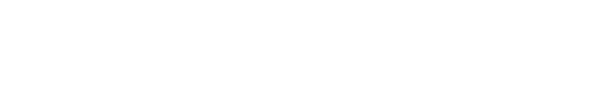

The river Als (Alserbach, from the Celtic als for stream (Bach) and olsa for alder (Erle)), which is recognised in the name of Vienna’s 9th District, Alsergrund, is first mentioned in documents. In the 19th century, the area became increasingly swampy, and between 1840 and 1846 the Alserbach was diverted for hygienic reasons.

The village of Siechenals (the German name is a play on the sluggish flow of the river) was situated on the banks of the Alserbach.

The diseases brought during the crusades meant that many people needed medical attention, and were taken to infirmaries (Siechenhäuser) in the surrounding towns (e.g. St. Johann an der Siechenals).

13th century

Foundation of the Heiligengeistspital for the care of the poor - the first autopsy in Vienna takes place here (1404).

14th century

St. Lazar hospital was founded in the village of Siechenals to care for lepers.

1302

The first clearly documented and judicially ordered post-mortem examination took place in Bologna.

1365

The University of Vienna is founded (Alma Mater Rudolphina Vindobonensis).

The Medical Faculty is a founding member of the Alma Mater Rudolphina Vindobonensis.

1399

The first records of events at the Faculty of Medicine date from May 1399, in the University Archives, Acta Facultatis Medicae Universitatis Vindobonensis.

15th century

The Italian professor Galeazzo di Santa Sophie (died 1427) performed the first autopsy for teaching and demonstration purposes at the Heiligengeist Hospital. The hospital founded in the 13th century was destroyed during the first siege by the Turks and was never rebuilt (now the Technical University of Vienna).

The first autopsy was carried out in the presence of doctors from the Faculty of Medicine and “scolares”, various scholars. Those attending the autopsy had to pay a fee. Once all expenses had been covered, the remaining amount collected was used to purchase a seal for the Faculty of Medicine.

In subsequent years, the university archive Acta Facultatis Medicae Universitatis Vindobonensis makes passing reference to autopsies carried out on those who had been executed. Observers included paying students and professors from various faculties, clerics and non-academic healers.

"The Faculty of Medicine hereby announces that, in the honour of God, for the benefit of mankind, in the honour of Vienna’s higher education establishments and for the particular benefit of medical scholars and students and after many requests by the scholars, a highly useful dissection of a human body, which we call anatomy, will be held in the presence of every doctor of this faculty in the coming days. Consequently, whoever wishes to attend this event, to see internal and external body parts, and to hear their names and explanations, may they kindly proceed to the building of the medical doctors today [at the time stipulated], in order to hear the explanations and intentions of the Faculty of Medicine [in this respect]”

In the first half of the 15th century, post-mortem examinations were presumably only carried out when there was sufficient interest or when students requested them. Post-mortems took place in a solemn setting, during which wine and confectionary (a mixture of various substances, covered in honey, which was intended to prevent nausea) were serverd. A requiem was then read in the presence of those present, and the body was laid to rest.

It is believed that the “Vienna Hospital” [Wiener Spital] mentioned in the Acta Facultatis Medicae Universitatis Vindobonensis was in fact the Heiliger Geist hospital, where post-mortems took place in its bathroom. The body was then buried in the St. Antonius Cemetery, which belonged to the hospital. Only in exceptional cases were autopsies carried out at the medical facutly itself.

In May 1452, the Faculty of Medicine selected a woman from among several condemned criminals sentenced to undergo an autopsy at the Faculty after her execution. Only medical doctors were allowed to attend the autopsy. Students, some of whom had already paid a fee to attend, were excluded after the woman was selected, although their money was refunded. After the autopsy, rumours spread that the woman had been pregnant. A pregnancy would have meant that a stay of execution should have been granted. Although this was denied by the Faculty, the fact that such special arrangements were made for this post-mortem examination leaves room for speculation.

Until the middle of the 17th century, only the bodies of criminals sentenced to death were subjected to an autopsy.

From 1672 onwards, the bodies of people who had died in one of Vienna’s hospitals could also be used for anatomical demonstrations (Horn, 2002 and 2004).

16th century

1532

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, Emporer Charles V's elaborate procedure for the sentencing of capital offenders (Halsgerichtsordnung), provided for the involvement of physicians in the judicial process when assessing medical issues.

So eyner geschlagen wirdt vnd stirbt, vnd man zweiffelt ob er an der wunden gestorben sei

147. Item so eyner geschlagen wirt, vnnd über etlich zeit darnach stürb, also das zweiffelich wer, ob er der geklagten streych halb gestorben wer oder nit, in solchen fellen mögen beyde theyl (wie von weisung gesatzt ist,) kundtschafft zur sach dienstlich stellen, vnd sollen doch sonderlich die wundtärtzt der sach verstendig vnnd andere personen, die da wissen, wie sich der gestorben nach dem schlagen vnd rumor gehalten hab, zu zeugen gebraucht werden, mit anzeygung wie lang der gestorben nach den streychen gelebt hab, vnd inn solchen vrtheylen, die vrtheyler bei den rechtuerstendigen, vnd an enden vnd orten wie zu end diser vnser ordnung angezeygt, radts pflegen.

Von besichtigung eynes entleibten vor der begrebnuß

149. Vnnd damit dann inn obgemelten fellen gebürlich ermessung und erkantnuß solcher vnderschiedlichen verwundung halb, nach der begrebnuß des entleibten dester minder mangel sei, soll der Richter, sampt zweyen schöffen dem gerichtschreiber vnd eynem oder mer wundtärtzen (so man die gehaben vnd solchs geschehen kan) die dann zuuor darzu beeydigt werden sollen, den selben todten körper vor der begrebnuß mit fleiß besichtigen, vnd alle seine empfangene wunden, schleg, vnd würff, wie der jedes funden vnd ermessen würde, mit fleiß mercken vnd verzeychen lassen.

17th century

1621

Paolo Zacchia (1584 - 1659): Quaestiones medico-legales (1621-1650): First systematic manual for forensic medicine.

1630

Deaths in the city were registered by the "Totenbeschreibeamt" records of external examinations dating back to 1648 are still held at the City and Regional Archive of Vienna.

1656

The "Bäckerhäusel" (close to today’s Boltzmanngasse / Währingerstraße) was also used as a place for sick people to convalesce.

1657

The "Kontumazhof" (a hospital for diseases between today’s Währingerstraße and Van Swieten Gasse) was built and later became the military garrison hospital of the City of Vienna.

1693

Johann Theobald Frankh, the founder of the hospital in Alsergasse (today's Alserstrasse), intended it to be a hospital for wounded soldier. Contrary to this original intention, it was used more for the accommodation and care of unit soldiers and poor people.

1694

The Home for the Poor and Invalid was built on Frankh’s land – completed in 1697 (today: first courtyard of the former general hospital).

Johann Theobald Frankh, the sponsor of the hospital on Alsergasse (today’s Alserstrasse) intended for wounded soldiers to receive care at the hospital. In contrast with this original intention, it served more to accommodate and care for soldiers who were unfit to serve and poor people.

In 1697 and 1726, the first and second courtyards were completed, corresponding to the first and second courtyards of the former general hospital (Altes Allgemeine Krankenhaus) today. The second courtyard, once called Ehehof or Witwenhof (marriage or widows’ courtyard), is now known as the Thavonahof after its patron, Freiherr von Thavonat. The hospital was extended again between 1730 and 1752 (Weiß, 1867 and Swittalek, 2012).

1732

The City of Vienna bought the land next to the Kontumazhof (a site for quarantined patients) and turned it into a cemetery.

1756

An Anatomic Theatre was opened at the University of Vienna (today: Dr Ignaz-Seipl-Platz 2, 1010 Vienna - Academy of Sciences).

Physiological and pathological anatomy, as well as animal anatomy, was taught in the course of medical classes in the “well-appointed Amphitheatrum anatomicum.” It was open to physicians, surgeons (non-academic skilled healers), students and artists. Physicians and surgeons were able to perform post-mortems here themselves for a small fee. When the anatomical theatre was built, special attention was paid to ensuring the smooth delivery of corpses, good lighting and proper hygiene. Most of the corpses came from hospitals in Vienna.

1761

Giovanni Battista Morgagni published his seminal work "De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis" (On the Seats and Causes of Diseases as Investigated by Anatomy) – this sentence was used by way of dedication on the gables of the Institute of Pathology.

1768

31.12.1768: Archduchess Maria Theresia enacted the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana, a uniform penal code for Austria and Bohemia.

1770

30.03.1770: The external examination of corpses was made compulsory by order of Maria Theresia and could only be carried out by physicians. Coroners had to be certified by the Faculty of Medicine.

The "Hauptsanitätsnormativ", a generally health law for the lands of the Monarchy, was introduced. The Sanitäts- und Kontumazordnung brought uniformity to the entire health system. The health and well-being of the population became a matter of state concern.

1775

Elements of forensic medicine were taught during lectures on surgery in order to familiarise students and physicians with external examinations of corpses.

1783

The garrison hospital was built on the former land of the Kontumazhof to care for wounded soldiers.

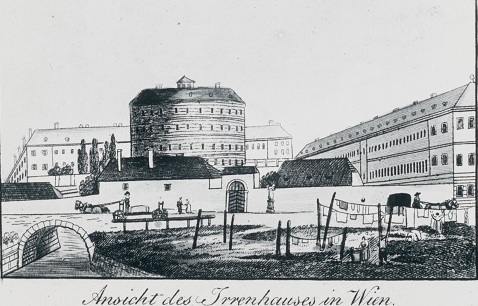

1784

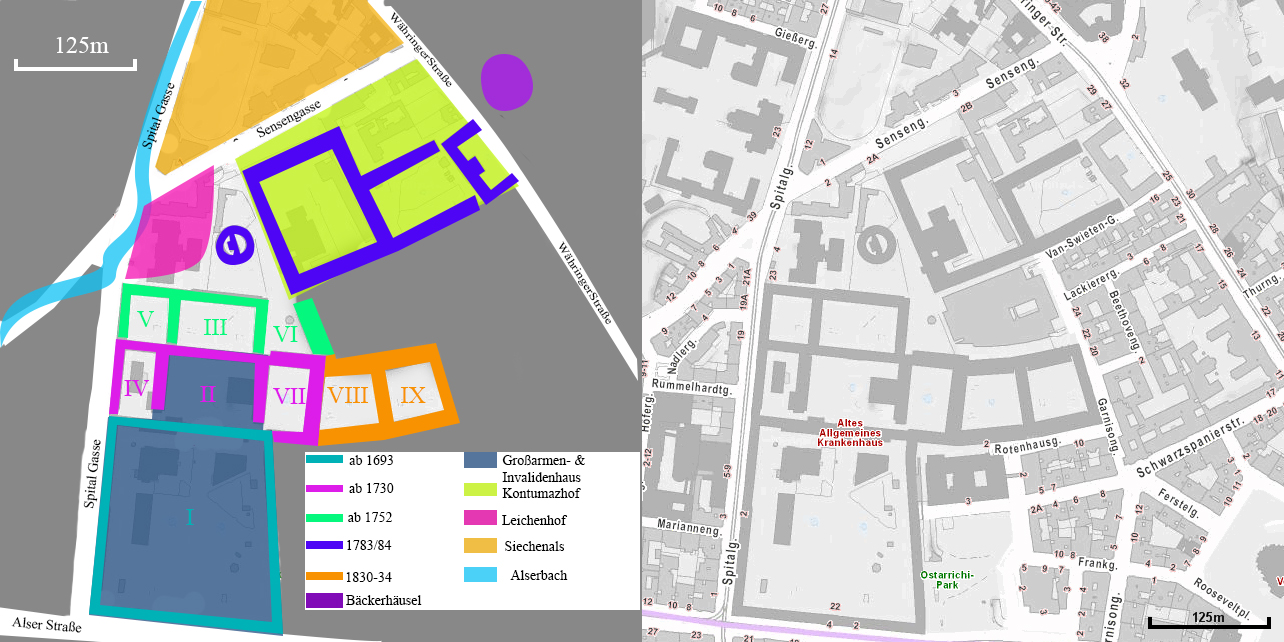

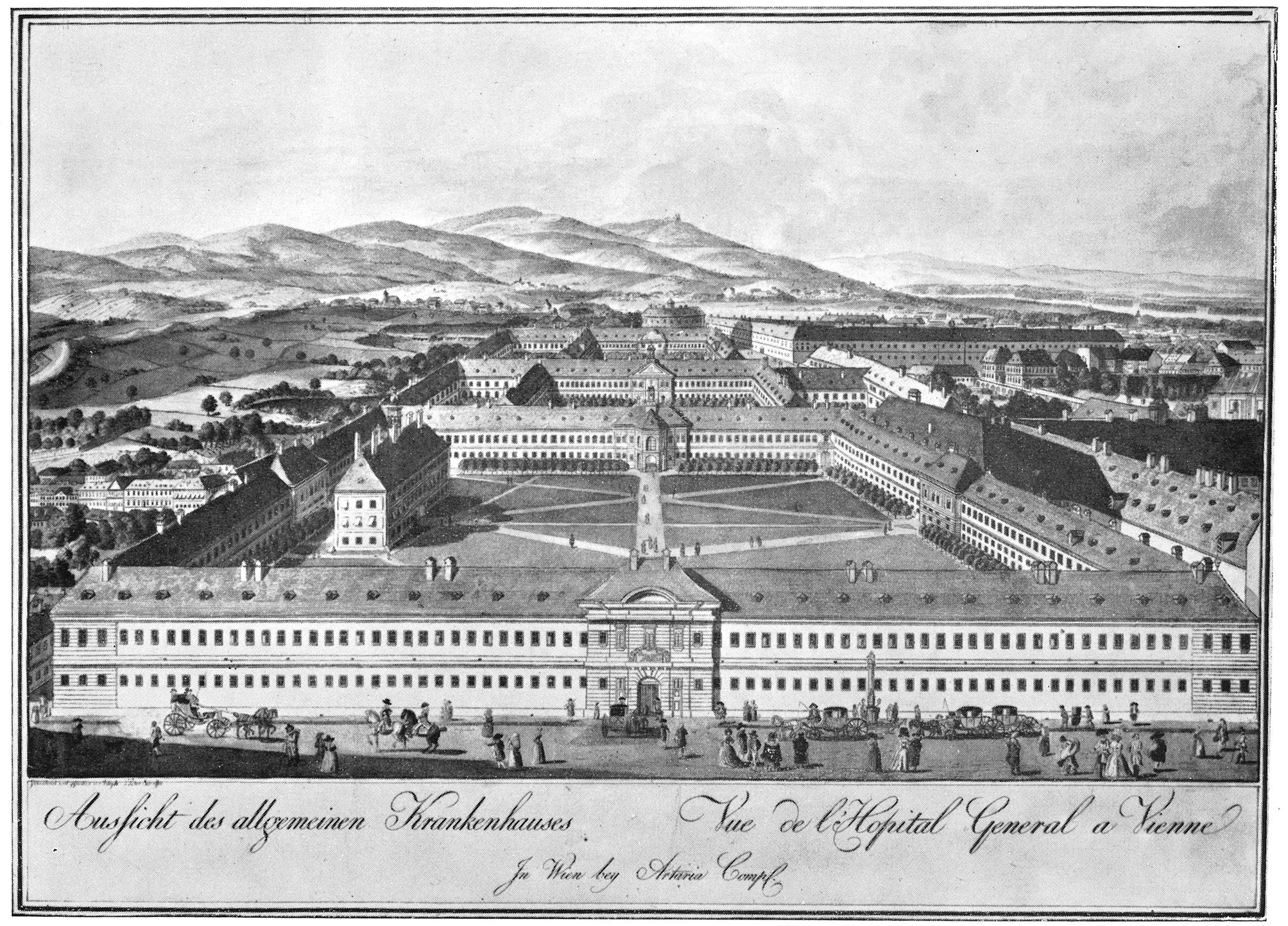

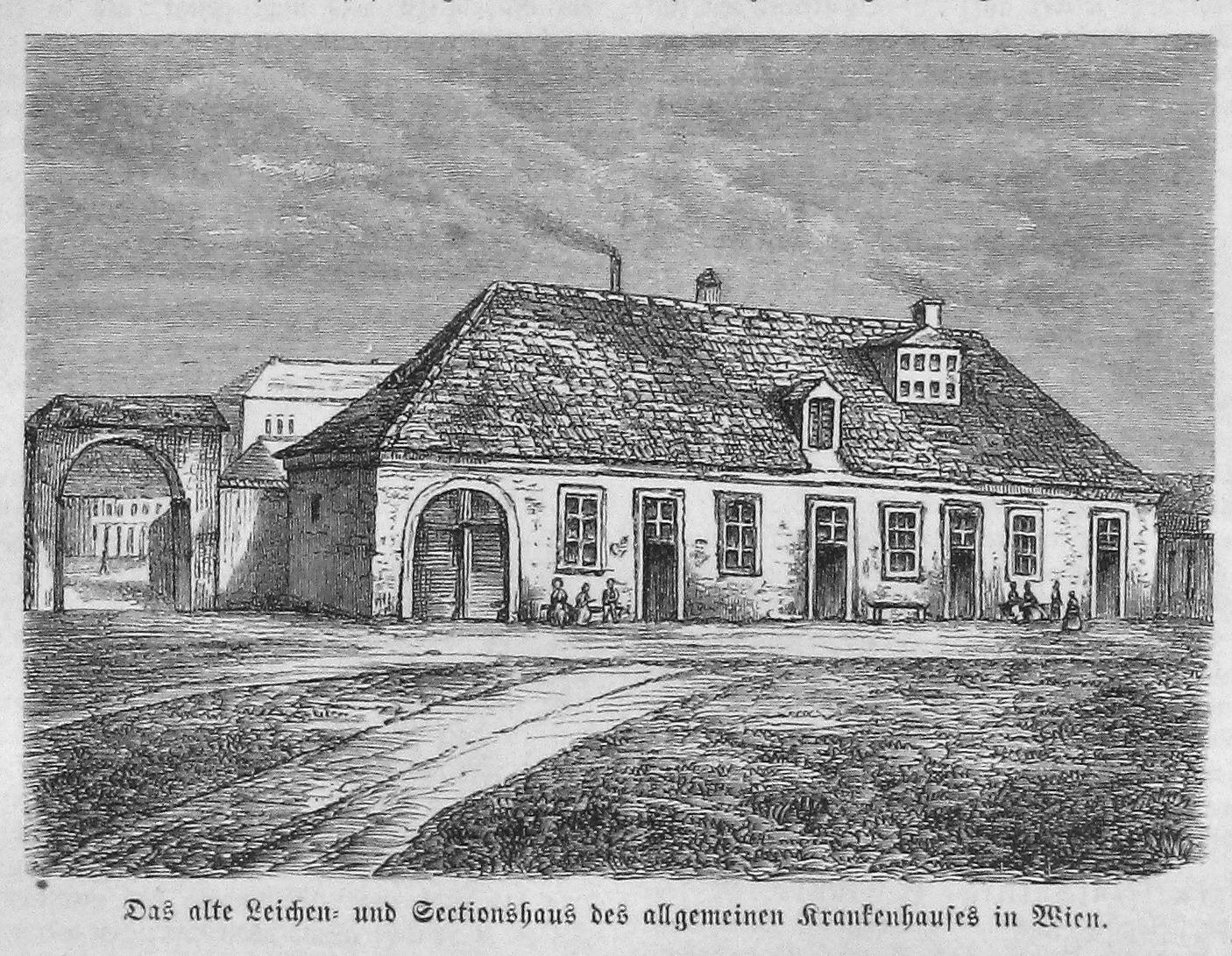

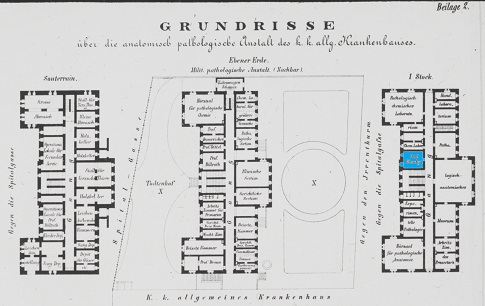

Joseph II (1741 - 1790) opened the Vienna General Hospital on 16 August 1784 to care for and provide solace to sick people (“saluti et solatio aegrorum”) based on the Home for the Poor and Invalid (today, courtyard 1 to 7 of the former general hospital). A mortuary was built at the north-east end of the facility next to the straw warehouse (hence the German name Strohhof or Leichenhof; courtyard 10 of today’s former general hospital).

Official post-mortems were transferred to the two youngest surgeons. Together with the city surgeon, they formed a commission in which the city surgeon performed the actual autopsy.

When Joseph II. (1741 - 1790) realised that the Home for the Poor and Invalid was being used as living quarters for poor civilians and unfit soldiers and not as a hospital, which was the original intention, he decided to close it. In its place should come a modern hospital, based on the example set by Paris’s main hospital, Hôtel-Dieu. When planning it, the focus was to be on cost efficiency, hygiene and medical provisions in line with the latest scientific advances. It was largely financed out of the emperor’s private fortune. Moreover, Joseph II insisted on each patient being given their own bed instead of as many as four people having to share a bed, which was the case in the Parisian hospital.

Joseph II commissioned his personal doctor, Joseph Quarin (1733 - 1814), with the redesigning and expansion of the Home for the Poor and Invalid in 1783. The result, after just 17 months of construction work, was a unique hospital complex which also included a maternity unit and an asylum in addition to it being a general hospital. A foundling hospital and sick houses (hospices) were located adjacent to the hospital. Around 2000 patients could be cared for in 111 sickrooms, in which men and women were separated. As it was presumed that the air in the hospital carried germs that caused illness, care was taken to ensure that sickrooms were properly ventilated by opening facing windows. There were four categories of sickrooms at that time. First-class rooms were single-bed rooms with individual care and multi-course meals, while the fourth-class rooms were for sick poor people and were free of charge.

Any woman, whether she came from an upper or lower class background, could give birth to their child anonymously in the maternity unit. If the woman did not want to keep the child, it was then taken into the adjacent foundling house.

A three-storey building was in the first courtyard, known as Stöckl, which house the “practical medicine school”. It enabled classes to be held at sick beds, something which was introduced by Maria Theresia’s personal physician Gerard van Swieten (1700 – 1772).

In 1988, the City of Vienna handed the building complex over to the University of Vienna. Today it is home to the University of Vienna campus for the 15 departments of the Faculties of Historical and Cultural Studies and of Philological and Cultural Studies.

1785

On 7 November 1785, the surgical academy was opened (today: Josephinum)

- Forensic medicine lectures were held as an ancillary subject by the professor for surgery and obstetrics for students training to become physicians at the aforementioned Josephine Academy.

1795

Johann Peter Frank (1745 – 1821), who had been holding lectures on forensic medicine and medical policing since 1785, was appointed a professor at the University of Vienna and also as director of the Vienna General Hospital.

- Proposal: Setting up a chair for state pharmacology

- Publication of the fundamental book System einer vollständigen Medizinischen Polizey (system of a complete medical policy)

19th century

1805

The Prussian Criminal Code was enacted with rules governing forensic external examinations and the performance of post-mortem examinations: Explicit instructions that a post-mortem had to include the three cavities of the body (chest, abdomen and head), and that the lungs of newborns should be tested to ascertain if the child was dead or alive when it was born (part 2, chapter 2 sections 164 and 166).

Vietz studied medicine and law, but was more interested in veterinary medicine. On 24 November 1805, he became a full professor of forensic medicine and police science in Vienna. He created a reference book containing his lectures on forensic medicine, which was only published after his death in 1818 by Josef Bernt. One of his main duties as professor of forensic medicine was to perform post-mortem examinations in the presence of students. The students had to write up a visum repertum on what they had seen and were even allowed to perform post-mortems under the supervision of the professor. This was part of the slowly establishing, practically oriented approach to teaching at the Vienna medical school.

Works:

- "Instruktion für die öffentlich angestellten Ärzte und Wundärzte in den k.k. österreichischen Staaten, wie sie sich bey gerichtlichen Leichenschauen zu benehmen haben."

(Bauer, 2004)

1808

A regulation was enacted which stipulated the Professor for State Pharmacology should be ultimately responsible for forensic post-mortem examinations, which students could now also attend.

1812

All post-mortems ordered by the courts and health authorities from the city and towns surrounding Vienna were carried out at Vienna General Hospital (AKH).

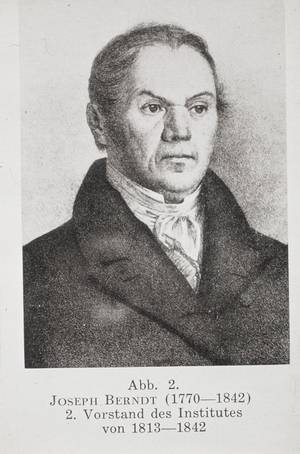

Born on 14 September 1770 in Leitmeritz in Bohemia, he received his doctorate in 1797 from the University of Prague. Bernt first held the Chair for Forensic Medicine set up in Prague in 1808, and became a full professor in Vienna on 25 June 1813. He worked to promote the smallpox vaccination and focused on issues related to hygiene and battling epidemics.

Works:

- "Systemisches Handbuch der gerichtlichen Medizin"

- Instructions on saving those who appear to be dead

- Work on smallpox vaccinations, plague infection, St. Vitus’ dance

- Founder of the hydrostatic lung test (determining if a newborn had already breathed – still in use today in a related form)

- "Über den Nachweis des Gelebthabens neugeborener Kinder während und nach der Geburt."

- The necessity to examine the circulatory system when assessing the cause of death in newborns, and the difference between foetal canals before birth and their changes after birth.

- Founder of the journal "Beiträge zur Gerichtsarzneikunde für Ärzte, Wundärzte und Rechtsgelehrte", precursor to the more well-known contributions to forensic medicine

- Promoting the pathology of sudden death

- "Pathologie des Ertrinkungstodes"

- "Tod durch Erhängen"

- Collection of visa reperta and forensic medicine reports to serve as a guide for students.

1815

The Office of the Official Head Medical Examiner of the City of Vienna was associated with the Chair of State Pharmacology.

1818

The prosector of pathology and anatomy was given responsibility for all post-mortems ordered by the health authorities and the courts à forensic medicine remains part of pathological anatomy until 1875.

The dissection chamber was extended, creating an anatomical theatre.

1821

An extraordinary chair for pathological anatomy was established and filled by Lorenz Biermayer.

1833

The University of Zurich was opened – official lectures in forensic medicine began.

The Practical Research Institute for State Pharmacology was founded in Berlin.

Born in 1803 in Deutsch Bielau, Bohemia. He studied at the University of Vienna and was an assistant for pathological anatomy under Rokitansky. On 23 September 1843, he was appointed full professor for forensic medicine. Kolletschka cut himself during a post-mortem examination and died shortly afterwards from blood poisoning.

Works:

- Über Pericarditis – highlights the connection between observing the patient on their sick beds and subsequent post-mortem examination

1844

Pathological anatomy was established as a dedicated discipline – Rokitansky was the first Ordinary Professor of Pathological Anatomy in Vienna.

1855

Enactment by the Ministries of Internal Affairs and Justice: Provisions for performing forensic external examinations.

Chair for Forensic Medicine was established at the University of Bern – a dedicated institute was only established in 1927.

1859

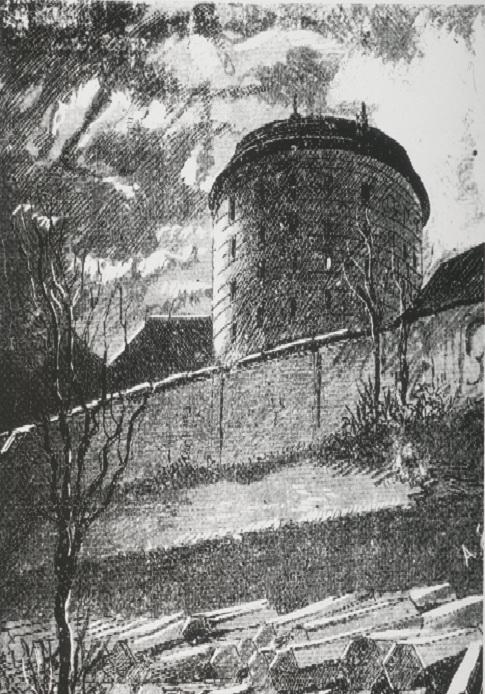

The Institute of Pathology and Anatomy (known colloquially as the "Indagandis Hof", after the dedication on the pediment, “Indagandis sedibus et causis morborum”, meaning "the study of the sources and causes of disease") was built on the site of the former mortuary. The working areas were located in the north wing of the first floor, with a chemical laboratory and a museum. The forensic funeral chamber and a commission room were located on the ground floor.

Born in Pilsen in 1808. He became an assistant at the Museum of Anatomy and Pathology in Vienna in 1839, before becoming prosector and professor of pathological anatomy in Prague. In 1848, he was called back to Vienna to take up the chair of Forensic Medicine, a position which he held until 1875. He succeeded in securing a separate office for the professor of forensic medicine in the mortuary of the General Hospital.

Together with Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky, Dlauhy moved to the newly built one-storey "Leichenhof" building in 1862 (now the Brain Research Center of the Medical University of Vienna).

1863

The Institute of Forensic Medicine was founded at the Karl Franzens University in Graz.

1869

A consecration chapel was built on the edge of today’s courtyard 10 of the former general hospital.

Following the example of Vienna, a chair for state pharmacology was established at the University of Innsbruck – the first holder of this chair was the future Director of the Vienna Institute, Eduard von Hoffmann.

1875

Chair for hygiene was established upon the opening of a dedicated Institute of Hygiene in 1908 on Kinderspitalgasse.

Born on 27 January 1837 in Prague. He studied at the University of Prague and received his doctorate in medicine in 1861. In the same year, he took up a position as an assistant at the Prague Institute for Forensic Medicine and was entrusted with the chair in a caretaking capacity following the death of the head at that time, Popel, in 1864. In 1869, Hofmann filled the newly created position of Chair for State Pharmacology in Innsbruck, before being called to Vienna in 1875.

Given that Hofmann was fluent in German, Czech, French and Italian, he had access to a wide range of literature on forensic medicine. He studied important cases in great detail using this literature and, by publishing these, made them accessible to other experts in the field. Hofmann recognised the value of the large number of corpses for post-mortems ordered by the health authorities or the courts which, thanks to him, were part of the duties of the institute and could be used for scientific and teaching purposes.

The building of the Institute for Forensic Medicine was extended in 1883 when a second floor and an auditorium were added. The working areas were moved to the south wing of the first floor and the museum was moved to the second floor. The auditorium, post-mortem room for forensic medical doctors and the laboratory were housed in the southern half.

Hofmann’s time as head of the institute also saw the death of Crown Prince Rudolph on 30 January 1889. Hofmann was involved in the post-mortem examination of the heir to the throne and proved suicide. Furthermore, evidence gathered during the examination indicated, according to Hofmann, that Rudolph acted in a state of extreme mental confusion. This made it possible for the body to be interred by the church.

Hofmann’s time as head of the institute also saw the death of Crown Prince Rudolph on 30 January 1889. Hofmann was involved in the post-mortem examination of the heir to the throne and proved suicide. Furthermore, evidence gathered during the examination indicated, according to Hofmann, that Rudolph acted in a state of extreme mental confusion. This made it possible for the body to be interred by the church.

Hofmann’s examination of the victims of the Ringtheater fire on 8 December 1881, in which the lives of more than 380 victims were claimed, brought further important findings for forensic medicine. Hofmann established the presence of carbon monoxide in the blood of charred bodies for the first time and demonstrated that smoke inhalation can be fatal. He provided ultimate proof here that the inhalation of smoke is a definitive sign of someone having been burned alive and the lack of carbon monoxide in the blood is an indication of someone being burned post mortem.

The "Wiener Freiwillige Rettungsgesellschaft", Vienna’s first rescue organisation, was established following the tragic events on 8 December 1881. Modern identification methods were used when examining the bodies, such as by using dental records.

Hofmann worked his whole life to give forensic medicine a scientific basis and used microscopy for his subject.

His services to science and healthcare were recognised by his being awarded the Order of the Iron Crown in 1884, lifting him to the status of knighthood. Hofmann was buried in an honorary grave in 1897 at Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

Works:

- "Die Respiration während der Geburt mit besonderer Rücksicht auf das Einatmen von Fruchtwasser als Hilfsmittel zur Erkenntnis des auf natürlichem Wege eingetretenen Todes der Neugeborenen (professorial thesis)."

- "Lehrbuch der gerichtlichen Medizin"

- "Atlas der gerichtlichen Medizin"

- "Über den plötzlichen Tod aus natürlicher Ursache"

- Development of an autopsy technique for children’s bodies

- Investigations and work on subjects including: suffocation, infanticide, tubal pregnancies, proving virginity and defloration

- Promoting the use of toxicology in forensic medicine

- Incorporating medical chemistry into forensic medicine

Was born in Vienna on 6 November 1857. He graduated with a doctorate from the University of Vienna on 7 December 1881. He was already active as a demonstrator at the Institute of Pathology during his studies.

He taught his students to document in detail all seemingly unimportant incidental findings. He placed particular emphasis on the pathological detection of poison, the pathology of sudden death and electropathology. He left the criminalistic side of the field, working with the courts and holding lectures for lawyers, to his first assistant Albin Haberda. In 1916, he took up the Chair for Pathological Anatomy.

Works:

- "Die Blutversorgung des Globus pallidus"

- "Die pathologischen Beckenformen"

- "Über den plötzlichen Tod aus natürlicher Ursache"

- Publisher of the 9th edition of Hofmann’s textbook

20th century

1909

Institute of Forensic Medicine established in Munich.

Born in Bochnia, Galicia, on 29 January 1868, Albin Haberda received his doctorate in 1891 at the University of Vienna. From 1889, he was a demonstrator at the Institute for Forensic Medicine and, in 1892, he became deputy forensic anatomist. Following the death of Hofmann in 1897, Haberda was appointed caretaker of the Chair for Forensic Medicine until this position was filled by Alexander Kolisko in 1898. Once Haberda actually took over the position of Chair in 1916, the Institute was enlarged, both in terms of the building and personnel numbers.

Works:

- "Die gerichtsärztliche Bedeutung von Rachenverletzungen an Leichen Neugeborener."

- "Die fötalen Kreislaufwege des Neugeborenen und ihre Veränderungen nach der Geburt."

- "Über das postmortale Entstehen von Ekchymosen."

- Resumption of the "Beiträge der gerichtlichen Medizin"

1922

The former military prosector building of the garrison hospital at Sensengasse 2 (its role as a military hospital was abandoned following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy after the First World War) was converted to the Institute for Forensic Medicine in 1922, now the Center of Forensic Medicine.

Anton Werkgartner was born in Mauthausen on June 5, 1890. After the so-called Anschluss of Austria to the German Reich, he first became acting head of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Vienna.

Fritz Reuter was born in Vienna on May 30, 1875, and was removed from office for political reasons.

- A chemistry lab for forensic medicine was set up

Forensic medicine during National Socialism

Following the annexation of Austria and the associated assumption of power by the National Socialists in 1938, the Vienna Institute for Forensic Medicine was subject to a process of “nazification” and not just through the field’s close work with the governing legal system.

With its integration into the NS biopolitics, forensic medicine played a key role in areas such as the selective births policy of the Nazis. The task of forensic medical doctors to identify “criminal abortions” was aimed at ensuring the preservation of “valuable public heritage”. Moreover, it prepared decisive reports for castration trials “to stop the spread of hereditary illnesses” and paternity reports “in order to rule out Jewish fathers”.

A cooperation existed between the Institute and the German Air Force from 1940, which led to many dissertations of German students being supervised.

Due to the good connections to Heinrich Himmler, SS Reichsführer and Head of the German Police, and Arthur Nebe, Head of the Reich’s Criminal Investigation Department, the Central Institute of Criminological Medicine was established in Vienna in 1943. Its aim was to prevent crime on the basis of racial biology. The alleged serial killer Bruno Lüdke was subject to a range of hereditary and anthropological tests at the institute before being subject to a fatal experiment, which reflected the most extreme form of National Socialism’s thinking on eugenics.

The role of Vienna’s forensic medicine during National Socialism is described in detail in the German-language book “Wiener Gerichtsmedizin im Nationalsozialismus" by Ingrid Arias and published by Verlagshaus der Ärtze.

Walter Schwarzacher was born in Salzburg on April 3, 1892. He was mainly concerned with chemical-physical aspects of bloodstains (bloodstain analysis).

Leopold Breitenecker (Head of the Institute 1958 - 1973)

- Renovation of the old section of the building – an additional floor was added to the side wings and a new laboratory building was created by extending the building along Sensengasse.

- The presence of carbon oxide in blood was proven.

- The Department of Serology and the Department of Anthropology were established.

- A place for the collection of forensic medicine specimens was finally created in the listed central part of the main building.

1967

Institute of Forensic Medicine was established in Salzburg.

Wilhelm Holczabek was born in Vienna on May 8, 1918. He

- created the definition of pain grading that is still valid today in criminal and civil law and

- significantly improved the detection of carbon monoxide (e.g. after poisoning) in blood and tissue samples from corpses.

Works:

- "Gerichtliche Medizin – Mutterdisziplin der begutachtenden Medizin, 1992"

- "Grundlagen und Praxis der Begutachtung von Verletzungen im Strafverfahren, 1987"

- A DNA laboratory for forensic medicine was established.

21st century

2001

Manfred Hochmeister was appointed Professor for Forensic Medicine.

2002

The carve out of the Faculty of Medicine from the University of Vienna was decided upon in the Universities Act.

- The DNA laboratory was accredited

The autonomy of the Medical University of Vienna (formerly the Faculty of Medicine) came into force.

Director of the Institute for Medical Chemistry

interim Head of the Department 01.12.2008 - 31.03.2010

2010

Daniele U. Risser is appointed Professor of Forensic Medicine and takes over as Director of the Center of Forensic Medicine ZGM (formerly Department of Forensic Medicine DGM).

- ZGM facilities and the DNA central laboratory were renovated and brought into line with the latest technological advances

- The Division of Forensic Toxicology was carved out and included as the Unit of Forensic Toxicology in the Clinical Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Clinical Department for Medical Chemistry Laboratory Diagnostics at the Vienna General Hospital.

- The Division of Forensic Molecular Biology was carved out and turned into an independent limited company (Forensisches DNA-Zentrallabor GmbH of the Medical University of Vienna)

- The post-mortem area was renovated and regular post-mortem activities were resumed at Sensengasse 2 after having been carried out in hospitals belonging to the Vienna Hospitals Association for several years

- The Units of Forensic Anthropology and Forensic Gerontology was established

since 18.12.2021 executive director

- ISO certification

- new laboratory information management system (LIMS) from 18 July 2023

- Forensic entomology