Forensic entomology is the use of the knowledge of insects to solve criminal cases, especially to determine the time of death.

Using forensic methods, it is generally feasible to determine the post-mortem interval in the first 48 hours after death. However, if the death occurred longer ago and the body begins to decompose, it becomes increasingly difficult. From this point onwards, forensic entomology is utilised.

The work begins at the discovery locality of the corpse, where the prevailing corpse fauna and the immediate surroundings must be examined, as insect larvae can migrate away from the corpse at a certain point to pupate. This is followed by the correct preservation of the insect larvae and pupae found, although some specimens must be caught alive for species identification. A temperature logger or climate logger must be set up to record the environmental conditions that are critical for calculating the post-mortem interval.

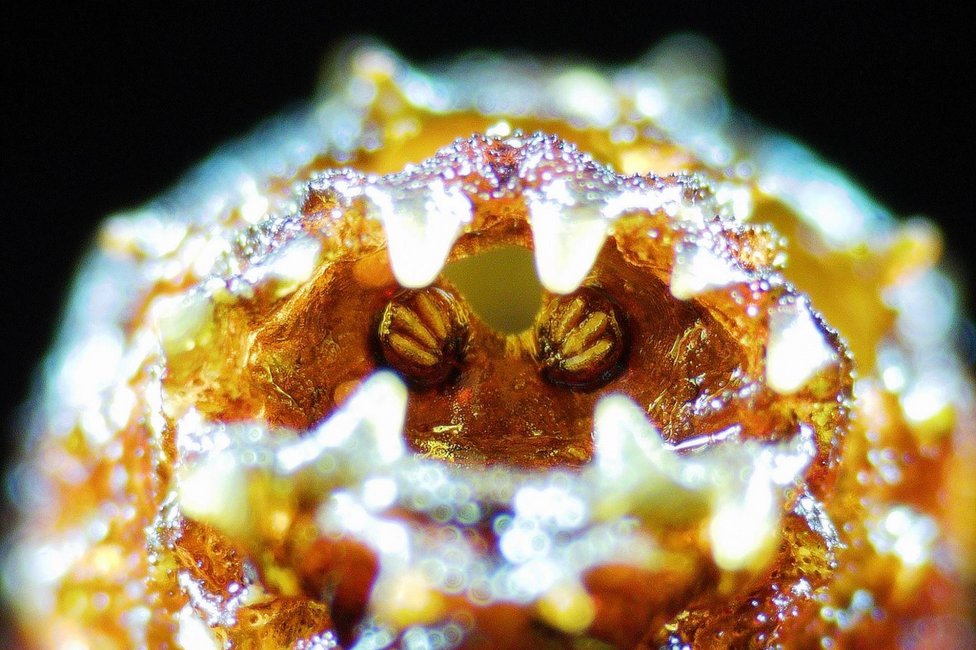

In the laboratory, the preserved, living animals are bred to the adult stage and the species is determined under the microscope.

Once the species has been determined, age parameters are compared with our own controlled research or published studies in order to narrow down the post-mortem interval in combination with the recorded climatic conditions.

To summarise, the aim of forensic entomology is to use insects to determine the post-mortem interval.

Current Research

It is undisputed that climate change is currently occurring. Our ecosystems, which have adapted to stable environmental conditions and factors over time, are now facing sudden changes of anthropogenic origin. The animals, plants and fungi in these systems must overcome these challenges in order to thrive and survive. While warm-blooded animals have their own challenges to overcome in relation to climate change, the impact on cold-blooded animals, such as insects, should not be neglected, especially when their life cycles are the focus of a scientific discipline.

This is especially relevant to the work of forensic entomologists, as their work to calculate the minimum PMI (post mortem interval) is based on careful observations and measurements of the life cycles of blowflies, among others, carried out under controlled conditions. As mentioned above, this laboratory data is then used together with corrected temperatures from crime scenes and weather stations to estimate the time of death.

In 2023, the average annual temperature was around 3°C higher than in the early 1980s, when the first studies on native blowflies were published. Although this difference may seem small at first, it can be critically important for insects, as it can determine whether they can survive or not. It can also be assumed that populations of the same species in northern or southern regions are adapted differently to species in Austria. It is therefore of enormous importance to generate up-to-date data with native animal populations in order to be able to estimate the most accurate estimation of the post-mortem interval.